The CDMO (Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization) industry involves companies that provide comprehensive services to pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors, ranging from drug development to manufacturing. The sector is currently in vogue due to changing macroeconomic trends across the world such as cost control, quality assurance and confidentiality of intellectual property. There are three key trends driving the CDMO industry: Eroom’s Law, the Inflation Reduction Act and Patent Thicketing. These trends showcase the growing pain for the pharmaceutical innovators, which is expected to result in a shift towards dependence on CDMO players to manage costs effectively.

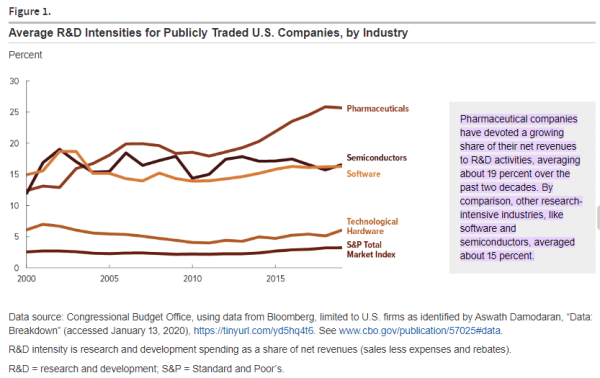

The biggest pharmaceutical market for the world is the United, accounting for roughly 50% of the global pharmaceutical sales revenue. In the US, pharmaceutical companies spend around 20% of their revenue on research and development, making it the most important market for innovators. For these reasons, the United States is considered the key market in this publication.

Eroom’s Law

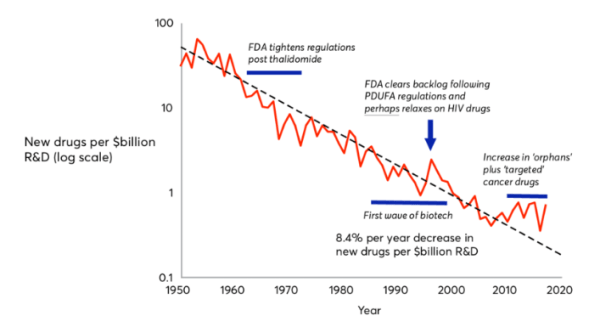

To understand CDMOs, one must first understand the nature of drug discovery. They key idea behind the drug discovery business is Eroom’s Law (the inverse of Moore’s law); based on the observation that drug discovery becomes slower and more expensive every day. The cost of developing a new drug has doubled every nine years since 1950, which means the money we spend to develop just one successful drug today would have covered the cost to develop 90 drugs 70 years ago, after adjusting for inflation. The average R&D to marketplace cost for a new medicine is nearly $4 billion, and can sometimes exceed $10 billion. In 2023, innovators spent around 14% to 50% of their revenues on research and development for new drugs, with the average being 19%.

Source: Jones et al (2018)

Why have the cost increased at such a high rate?

- The 'better than the Beatles' problem: The cost of drug development has increased significantly due to the evolving nature of medical advancements. Breakthroughs like antibiotics and vaccines have transformed healthcare, saving countless lives and improving quality of life. For instance, the discovery of penicillin in 1928 drastically reduced deaths from bacterial infections, demonstrating the power of early medical innovations. Today, as medical science tackles more complex diseases, achieving new breakthroughs has become harder. It requires deeper knowledge, advanced technology, and substantial financial investment, all while meeting rigorous regulatory standards. This complexity contributes to higher costs and challenges in developing new medicines.

- The regulatory problem: In the past, when the long-term effects of drugs were uncertain, FDA clearance was easier to obtain due to lack of knowledge. However, with increasing awareness of drug side effects and public concerns, the FDA has become more vigilant in safeguarding consumer interests. Over time, regulatory hurdles have intensified as the FDA now requires more comprehensive data from clinical trials to ensure the safety and efficacy of drugs. Moreover, companies must conduct long-term post-marketing studies even after approval, adding substantial costs and time to the drug development process. While these strict requirements enhance patient safety and drug effectiveness, they also significantly increase the complexity and expense of bringing new drugs to market.

- Economic and Market pressures: Economic and market pressures in the pharmaceutical industry have intensified in recent years, driven by rising research and development (R&D) costs. This increase is attributable to the adoption of more sophisticated and costly technologies, escalating labour expenses, and the demand for extensive preclinical and clinical testing. Simultaneously, heightened competition and market saturation have further compounded these challenges. Multiple companies compete to develop treatments for prevalent diseases, which makes the quest for novel therapeutic areas increasingly challenging. Consequently, pharmaceutical companies are compelled to invest more resources into researching lesser-known or more complex diseases, which adds to the overall financial burden and strategic complexity of drug development initiatives.

The high costs in drug development have far-reaching consequences across key stakeholders. Firstly, these costs make innovators less willing to take risks on potentially life-saving drugs that may not yield high profits, leading to fewer breakthrough treatments reaching the market. Secondly, these expenses, either directly or through increased insurance premiums, burden patients who urgently need these medications. Third, the escalating medical costs strain government budgets, affecting public healthcare expenditure.

The Inflation Reduction Act

In August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law, allocating federal funds to various initiatives aimed at reducing carbon emissions, lowering healthcare costs, funding the IRS, and enhancing taxpayer compliance. Biopharma and biotech companies are particularly focused on provisions targeting prescription drug prices for Medicare patients.

One key provision allows Medicare to negotiate directly with biopharma and biotech firms to lower drug prices. Eligible drugs must be among the highest in Medicare spending, lack generic or biosimilar equivalents, and have been on the market for specified durations (7 years for small molecules, 11 years for biologics). The government identified the first set of ten drugs for negotiation, with new prices set to take effect from January 2026. A total of 60 drugs will undergo negotiation by 2030. This provision is expected to disproportionately impact high-cost Medicare drugs and small-molecule therapies. Although it applies solely to the Medicare population, price adjustments could potentially influence commercial payer negotiations and reset pricing for Medicaid and other entities.

As a result, the most profitable patented drugs would face pricing problems due to the implementation of the act. While the first 7 years for small molecules (and 11 for biologics) remain patent protected, the period may not be enough for the company to make a suitable return on investment and generate enough returns to reinvest in new drug discoveries. The initial period after drug approval requires extensive drug marketing and sales usually take multiple years to peak. As the Act aims to reduce the number of years of peak sales, such firms face huge profitability risks unless they are able to cut costs drastically in both the clinical phase and commercial phases.

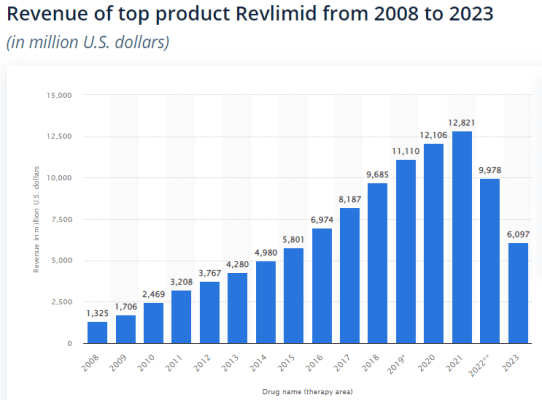

Source: Statista

For example, Revlimid, an oncological drug marketed by Bristol Myers was approved by the FDA in 2005 and retained exclusivity until 2022. The combined sales between 2008 and 2012 were lesser than the annual sales in 2021 showcasing the exponential effect of time on drug sales, and how most value of each new drug is realised a decade after launch. In this particular example, 2012 marks the 7th year since the approval of the drug. Due to the high expected loss in sales due to the Inflation Reduction Act, pharmaceutical innovators may be forced to increase prices faster due to the shorter timespan available to generate returns, or cut costs significantly.

Patent Thicketing

Patent thickets are formed when a company obtains a large number of overlapping patents related to a single product, making it difficult for competitors to develop similar products without infringing on those patents. Multiple patents may encompass various aspects of a drug, such as the antibody itself, its formulations, methods of usage, manufacturing processes, administration devices, and packaging methods. Given the necessity for biologics to be administered through injections, patents on administration devices often hold significant importance.

Due to the possibility of obtaining multiple patents within these categories, different aspects of a drug and its manufacturing processes may be covered by numerous patents. Consequently, a collection of patents typically surrounds each product. However, during the early stages of development, it is often unclear what the final commercial product will entail.

In the United States, where the patent system operates on a ‘first to file’ basis, innovators generally file composition of matter patents early to secure their rights. These filings occur well before the specific active moiety (a part of the chemical structure of a molecule) intended for clinical use is determined and certainly before the final product composition is established for patient use.

Subsequent patents are typically filed later in the development process, once the active moiety is clearly defined and the formulation and treatment methods are developed. This occurs significantly after the initial drug discovery phase has concluded.

A recent study, conducted by the University of Colorado, indicated that the effective patent life for a product is approximately 12 years. This period refers to the duration from drug approval to patent expiration, rather than from the patent filing date. It is noteworthy that this duration is significantly shorter than the standard 20-year term from filing. To achieve patent protection extending beyond the 12-year regulatory exclusivity period granted by the FDA for biologics license applications (BLA), biologic innovators typically file additional patents covering various aspects of their product beyond the basic composition of matter.

Generic drug makers wishing to make a copycat version of a branded drug generally have to challenge the patents in court. But merely listing a patent in the Orange Book (FDA approved drug products) automatically triggers a 2 and a half year delay of FDA approval of a litigating generic competitor. Patent thicketing has been one of the best methods to keep generic competition, who pose significant risks to profitability, at bay. The entry of generic drugs after the end of exclusivity severely reduces the price of the drug by as much as 60-80% within one year of loss of patent protection. Such generic manufacturers are often based in countries such as India, where the cost of production is significantly lower, making innovators unable to compete in a free market.

In short, innovators use patent thicketing to increase their exclusivity period to generate higher profits. While patent thicketing makes sense of pharmaceutical companies which have to generate returns for shareholders while maintaining the ability to reinvest capital in innovation, the cost is borne by consumers. In the eyes of Lina Khan, the commissioner of the FTC, consumers should not bear such high costs.

Since she took charge of the Federal Trade Commission in 2021, the institution has challenged the validity of over 100 drug product patents, focusing on devices used to deliver medicines, like inhalers and auto-injectors, in an effort to increase competition and potentially lower some prices. Historically, Orange Book patents have been rarely challenged although there is a long standing procedure for such challenges. The challenge to patent thicketing poses a significant risk to the profitability of pharmaceutical innovators.

To continue exploring this topic and delve deeper into our insights, don’t miss out on Part 2 of our blog series. Click here to access it now!

...Already have an account? Log in

Want complete access

to this story?

Register Now For Free!

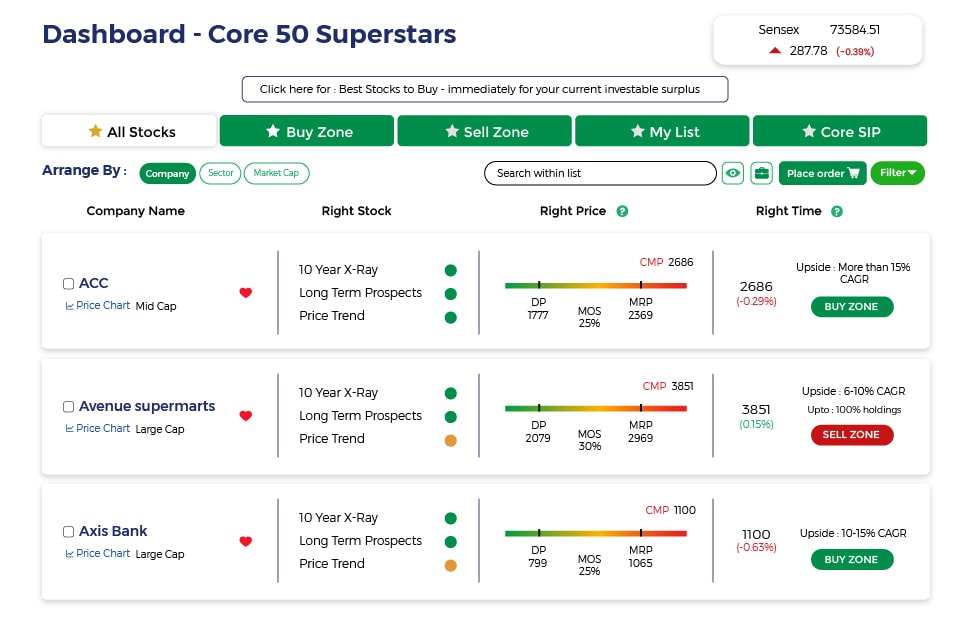

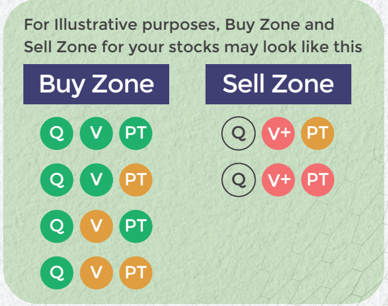

Also get more expert insights, QVPT ratings of 3500+ stocks, Stocks

Screener and much more on Registering.

Download APP

Download APP

Comment Your Thoughts: