In the world of value investing, Mr. Sundaram stands out with his unique approach, which he describes as "Commonsense Investing." His philosophy is straightforward: investment success can be achieved not only by making the right decisions but also by avoiding the wrong ones. Over his 29+ years in the investment industry, Sundaram has consistently demonstrated his ability to take significant contrarian positions, such as underweighting Technology in 1999, Infrastructure, Utilities, and Power in 2007, Midcaps in 2017, and excluding NBFC exposure in 2018.

Throughout his career, Sundaram has held prominent positions, including Manager (Research) at SBI Mutual Fund, Head of Research and Fund Manager at Zurich India Mutual Fund, Senior Portfolio Manager at HDFC Mutual Fund, Portfolio Manager at M3 Investment Managers (a family office), and CIO and Portfolio Manager at PGIM India Mutual Fund. His extensive experience and strategic insights have made him a respected figure in the investment community, exemplifying the principles of commonsense investing.

This blog is divided into two parts. Part 1 showcases the history of wealth creation and destruction across various cycles, while Part 2 highlights how an investor can navigate the markets to generate superior returns.

Let’s dive into Part One.

Contrarian Thinking

Mr. Sundaram contends that there are essentially two ways to succeed as an investor. Investors can either make money by doing the right things or avoiding the wrong things. Doing the right things involves finding out the growth prospects, assessing management quality and estimating profit and cash flow growth. Avoiding the wrong things however, requires investors to not buy weak businesses, not pay exorbitant prices and to stay away from the hype. According to him, avoiding wrong things is the domain of value investors like him.

Trying to get it right has its own challenges and relies on a lot of predictions. An investor must first figure out which industry will grow the fastest, followed by figuring out which company in this industry would grow the fastest. Once an investor finds answers to these questions, the investor must accurately predict the profit and EPS trajectory along with the macroeconomic and political trends. Finally, the investor must correctly estimate how much of all these factors are already reflected in the price.

This process lacks a long-term advantage due to two key reasons. First, it is difficult for an investor to be right about so many factors, especially given that the future is largely uncertain. Second, this method is highly competitive and attracts highly qualified investors looking at the same information. There is no information edge as every analyst has access to the same software, trade journals, and news. These factors make it difficult to earn excess returns over a long period.

The second method, avoiding wrong things, is the road less travelled. This merely requires an investor to avoid disasters in order to earn above average long-term returns. For an equity investor, the only disaster is permanent loss of capital. Permanent loss of capital can occur due to one of three reasons: (a) the company has a weak or deteriorating business, (b) the management is inept or dishonest, and (c) paying too much. Temporary loss of capital is an inherent feature of the markets and happens to all stocks irrespective of quality, and is unimportant. The focus of this framework is to lose less money rather than maximize returns.

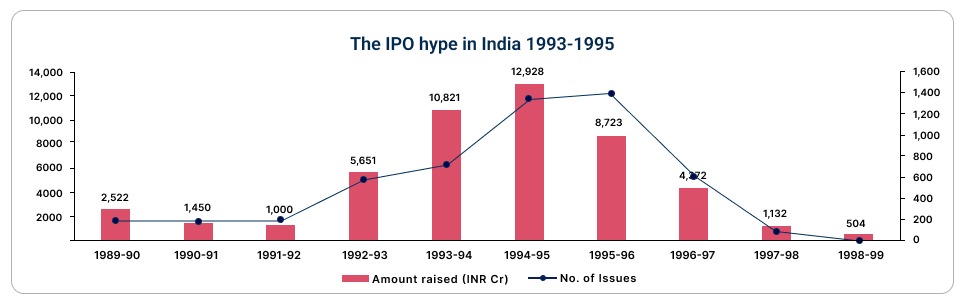

The Beginnings: The IPO Boom of 1993-1995

Source: CFA Society India

The IPO boom in India came shortly after the cessation of the office of the Controller of Capital Issues, allowing issuers of securities to raise capital from the market without requiring the consent of any authority. This resulted in a significant influx of new offerings through IPOs, with many debuting at or above par value. Consequently, it attracted more investors as providers of capital and prompted a rise in low-quality businesses opting for IPOs as recipients of capital. As the IPO bubble burst and a large number of such IPOs eventually lost investor capital, it became clear that outperformance is not as easy as it seems, and Mr. Sundaram’s team spent the better part of two years cleaning the portfolio after deciding on a quality-focused approach.

Entry Valuations Matter

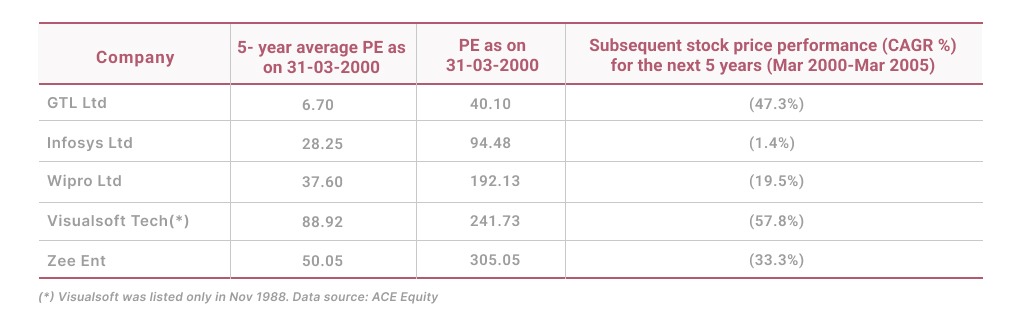

a) The Tech Boom

During the tech boom of 2000, ‘tech’ stocks became extremely popular as the benefits of computerization in the Western world were reaped by Indian IT players, particularly due to Y2K. This led to extremely high P/E valuations when compared to their historical means. This implied that the major chunk of wealth creation occurred due to re-rating rather than earnings growth, clearly indicating excessive valuations. Over the next 5 years, these stocks significantly eroded investor wealth on both an absolute and relative basis. Even though the businesses of quality companies such as Infosys grew at a high CAGR of nearly 36% between 2000 and 2006, there is no antidote for unreasonably high valuations.

Source: CFA Society India

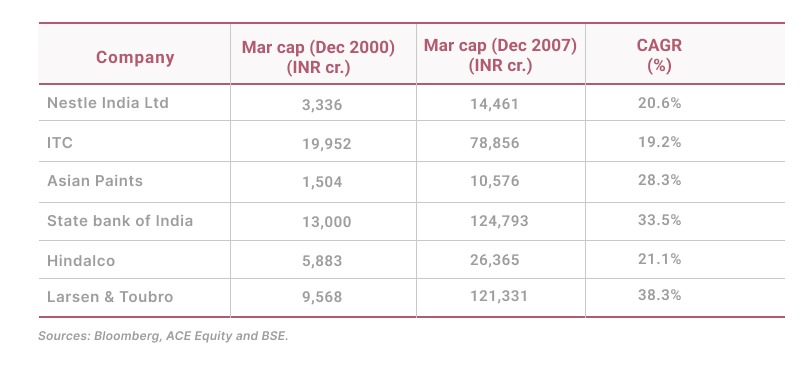

The excess in valuation was not widespread across the industry, and ‘old economy’ stocks were spared from market excesses. As a result, various high-quality businesses such as Nestle India, ITC, and Asian Paints were available at decent valuations. Even if an investor purchased shares of these companies at the height of the tech boom, he would have made spectacular returns till the end of the next bull market.

Source: CFA Society India

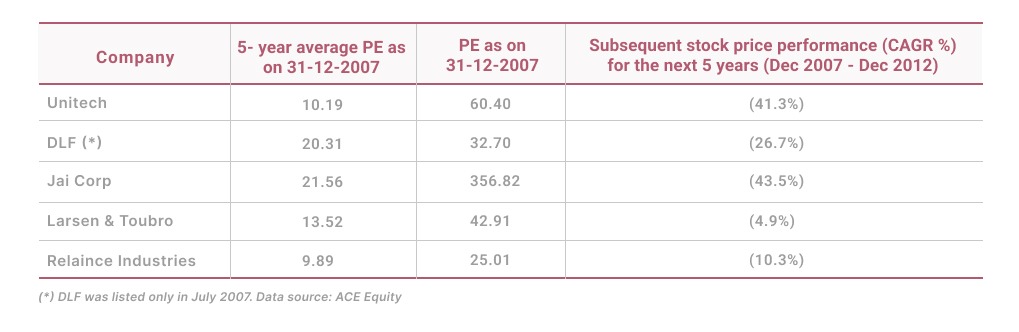

b) The Infrastructure Boom

The infrastructure and real estate boom of 2007 had the same story as the tech boom of 2000; only the names of the companies and the theme were different, the plot of excessive valuation remained the same. Companies that were shunned in the previous boom came to the forefront and began commanding extremely high valuations. However, these valuations were unsustainable and investors lost money over the next 5 years.

Source: CFA Society India

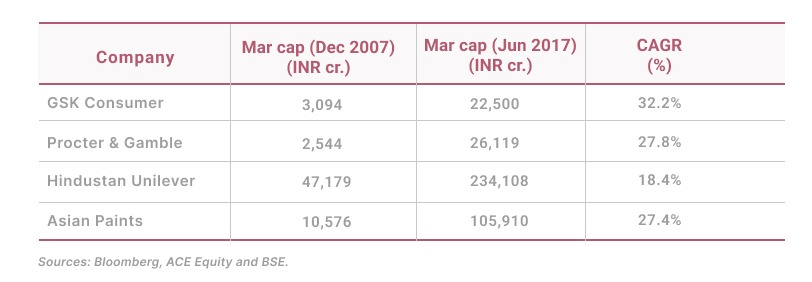

Similar to the tech boom, companies that were shunned in this bull market were available at low valuations even at the peak of the Bull Run. For example, Hindustan Unilever and Procter & Gamble were shunned by the investing community due to a lack of returns since 1999. As a result, these companies faced a strong derating in valuations which made them attractively priced. Even if an investor purchased shares of these companies at the height of the infrastructure boom, he would have made spectacular returns over the next 10 years, including the bear market that followed the Bull Run.

Source: CFA Society India

History may not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

To continue exploring this topic and delve deeper into our insights, don’t miss out on Part 2 of our blog series. Click here to access it now!

...Already have an account? Log in

Want complete access

to this story?

Register Now For Free!

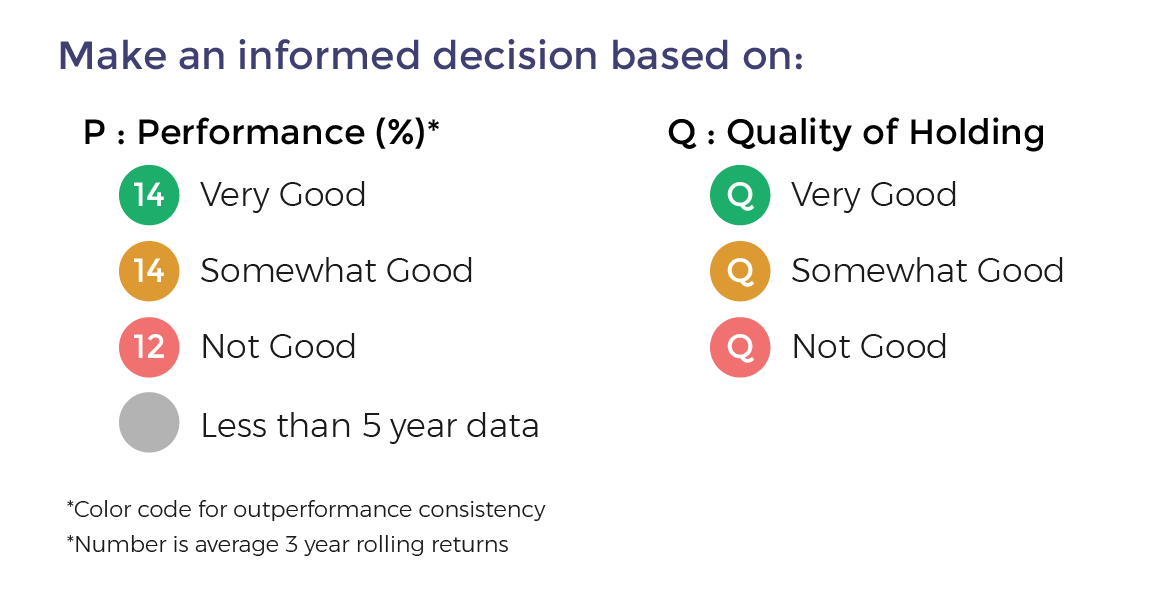

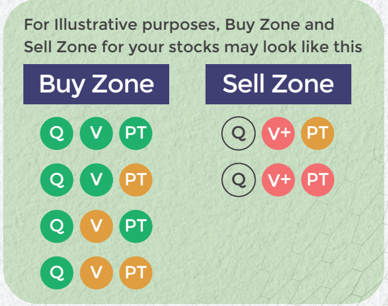

Also get more expert insights, QVPT ratings of 3500+ stocks, Stocks

Screener and much more on Registering.

Comment Your Thoughts: