Sanjoy Bhattacharyya is a seasoned investor and one of India's most respected value investors. He has over three decades of experience in the financial markets and is known for his deep understanding of value investing principles. Bhattacharyya has a strong academic background, with a PGDM from the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad.

He has held significant positions in the financial industry, such as the Chief Investment Officer of HDFC Asset Management Company. Bhattacharyya is also a founding partner of Fortuna Capital, where he continues to apply his value investing philosophy. His investment approach emphasizes long-term wealth creation through careful analysis of business fundamentals, focusing on companies with strong balance sheets, sustainable competitive advantages, and prudent management.

Bhattacharyya is also known for his educational contributions to the investing community through his writings and speaking engagements, where he shares his insights on market behaviour and investment strategies. Through one such speech, ‘The Difficulty of Being Good’, he tells us why investors fail to behave in a manner that makes them good investors. This article is divided into two parts. The first part discusses the element of uncertainty in investing while the second part discusses market wisdom and the behaviour of investors.

Let’s dive into Part One!

The Illusion of Control, Uncertainty and Futility of Precise Models

Humans crave certainty because it provides a sense of control, and we dislike feeling out of control. Throughout history, certainty has been vital to our survival. In early human evolution, a rustle in the bushes could indicate a predator, triggering an indiscriminate flight response. While this instinct, along with the habit of quickly drawing conclusions, has become deeply ingrained in human behaviour, the threats we face today are vastly different. Moreover, these reactions are triggered by the fast-thinking part of our brain, whereas investing requires the slower, more analytical side.

Our tendency to seek patterns makes us prone to finding meaning in random events, often drawing conclusions where none exist, in an attempt to feel certain in an uncertain world. As investors, we must accept that businesses are inherently uncertain because we cannot know everything, and the future is impossible to predict with complete accuracy.

Many investors derive a false sense of certainty from discounted cash flow models, which predict future business cash flows and lend an appearance of precision to the valuation process. Investors typically input assumptions they feel reasonably certain about, leading to seemingly reliable outputs. However, favourable assumptions often result in favourable valuations, sidestepping the uncertainty inherent in future predictions. It may be more useful to use these models to understand the general direction of a business based on its key value drivers, rather than aiming for precise price predictions.

Overconfidence, Illusions and the Key to Subpar Investment Results

The world tends to reward overconfidence, despite its well-known and well-documented risks. In the United States, a survey of individuals who had been involved in serious car accidents requiring hospitalization revealed that 92% of them considered themselves better-than-average drivers—an obviously absurd conclusion.

Overconfidence is often rewarded because people crave answers, even when those answers are wrong or unknowable. Moreover, individuals naturally seek rewards, even when they may not deserve them. On the other hand, admitting a lack of knowledge carries the risk of marginalization, as it suggests incompetence. Overconfidence can give investors an air of credibility, granting them access to better resources and more assets to manage.

The illusion of explanatory depth (IOED) is a cognitive bias that leads people to overestimate their understanding of a subject. Take a toaster, for example—everyone uses one and understands its basic function. However, if asked to explain how a toaster works, most would claim they know, even though they cannot describe the concept of electromagnetic resistance, which is essential to its function. We often believe we know more than we actually do. In an industry where the future is uncertain, many investors act confidently on their beliefs, despite the fact that these beliefs are often either wrong or unknowable, leading most to generate subpar returns.

Stories

Stories are more powerful than facts. They sell better than numbers because they are easier to understand and communicate, while grasping numbers can be far more challenging—yet crucial for making profits as an investor. A compelling narrative often leaves little room for disagreement or is so captivating that investors become convinced of its profit potential. When a story is particularly persuasive, investors may neglect to verify the numbers or simply overlook them because the future seems so promising. Even the most skilled businesspeople and investors can fall prey to the allure of a good story.

One of the most compelling stories of the 21st century was that of Theranos. Elizabeth Holmes, a Stanford University dropout, founded the blood-testing startup in 2003, aiming to revolutionize diagnostics by using just a few drops of blood. She used personal anecdotes, such as her fear of blood tests as a child, to sell her vision of a technology that would allow comprehensive testing with minimal blood. Her story attracted over $700 million in investments from billionaires like Rupert Murdoch, Larry Ellison, and the Walton family, pushing the company’s valuation to $9 billion at its peak. Her board was also filled with prestigious figures, including Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, and Jim Mattis. However, the numbers behind Theranos did not support the star-studded narrative, leading to Holmes’ conviction and imprisonment for fraud.

Rumsfeld’s Matrix

Investors cope with uncertainty in different ways, depending on the availability of data and the risks associated with their assumptions. When data is readily accessible, some investors believe that accumulating more information will lead to better decisions, turning them into "information junkies" who focus on the ‘known knowns.’ In other cases, when data is accessible but uncertainty remains high, investors may focus on the ‘unknown knowns,’ often confusing correlation with causation. This can lead them to draw conclusions based on unexplainable or unrelated factors, mistakenly treating irrelevant information as meaningful.

When access to data is limited and there exist factors one does not fully understand, known as situations of ‘known unknowns,’ investors may seek comfort in expert predictions, despite the high error rates associated with such forecasts. Finally, in cases of ‘unknown unknowns,’ where investors are unaware of what they do not know and both uncertainty and information scarcity are high, they may resort to relying on like-minded peers, market timing, or tracking macroeconomic indicators in an attempt to predict market trends and returns.

To continue exploring this topic and dive deeper into our insights, don’t miss out on Part 2 of our blog series which discusses frameworks, cycles, and behavioural insights. Click here to access it now!

Already have an account? Log in

Want complete access

to this story?

Register Now For Free!

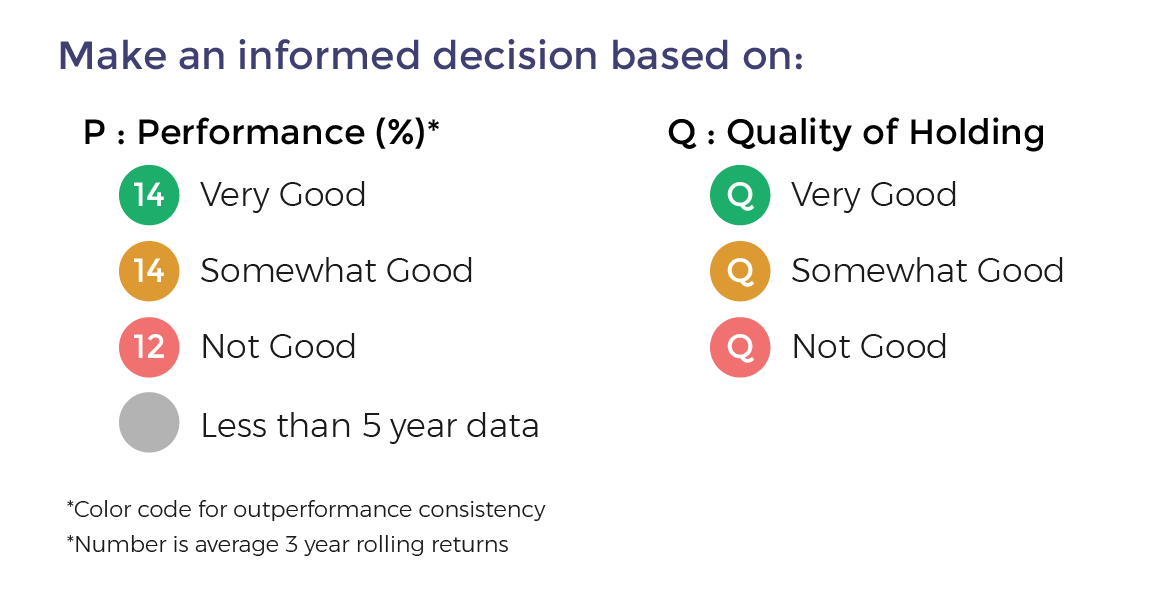

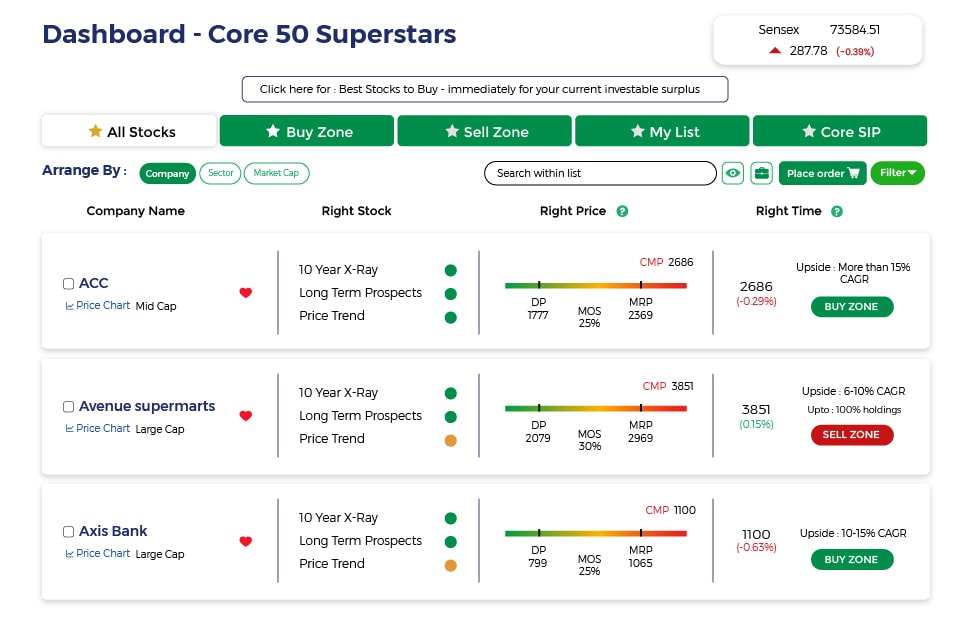

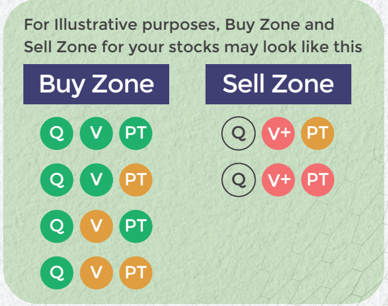

Also get more expert insights, QVPT ratings of 3500+ stocks, Stocks

Screener and much more on Registering.

Download APP

Download APP

Comment Your Thoughts: