Growth is one of the most important components of wealth creation. Growth often signifies that the business is healthy, has reinvestment opportunities and leads to an overall increase in shareholder value through dividends and price appreciation. However, not all growth is created equal, and growth can be value accretive, value destructive, or value neutral. Growth must always be valued with respect to the cost of capital. Growth is only beneficial when the present value of cash flows from such growth exceeds the current value of capital required to fund the growth. Simply, a rupee today not returned to shareholders should give them more than a rupee’s purchasing power in the future.

While the idea of avoiding value destructive growth is seemingly obvious, it is often ignored. Managements or owners may have grand ambitions and believe that the profits will follow once such ambitions have been achieved. Such ambitions take the form of size, market share or brand value all with low regard for returns. However, all forms of value destruction cannot and must not be attributed to the management as market conditions such as regulation, competition, substitution and value chain risks can erode shareholder value. While in some cases, the value destruction is seemingly obvious, in a lot of cases it is not. While managements and investors bet on the future, the future is uncertain and filled with anticipated and unanticipated risks, making value destruction possible in cases where value creation seemed obvious.

One can categorize value destructive growth into two categories, management driven and market driven value destruction. This article focuses on management driven value destruction since the focus should remain on the controllable aspects, rather than the uncontrollable. Additionally, the article does not cover fraud, which can be the most value destructive activity, as it is understood that illegal activity of any kind, would be value destructive.

Management driven value destruction is often one of the following types, or a combination of them:

1. Bad Acquisitions:

Companies often pursue growth through acquisitions, but if the integration fails or the acquisition was overpriced, it can destroy value. Between 70% to 90% fail, according to Harvard Business Review. The use of leverage in acquisitions can further destroy value as lenders are guaranteed payments, irrespective of performance.

While errors in valuation and integration are understandable reasons, such mistakes can be prevented by preventing such acquisitions at the board level. Ineffective board control is another reason for the failure of acquisitions. Boards, and their independent board members, are created in attempt to check the activities of the management on behalf of the shareholders. However, in reality, independent board members may not act as checks, but rather enforcers of the management, due to their relationships with members of the management or to continue their position on the board.

Example: Inept Boards and Bad Acquisitions

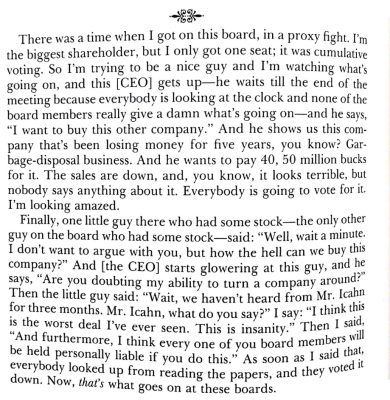

The following excerpt highlights the problem of ineffective governance at the board level.

Source: Twitter, Compounding Quality

2. Unrealistic Expectations:

Most businesses are cyclical, which highlights that profits and cash flows too are cyclical. While analysts, investors and managements agree with such a concept, they may be led to believe that there is a shift in the macroeconomic factors at the peak of the cycle. While the belief itself is not harmful, the actions of management as a result of such beliefs can lead to value destruction.

At the peak of a cycle, a business may earn a supernormal profit that does not represent its real earnings power. If the management believes that the returns are cyclical, they may use such profits to deleverage the balance sheet or return capital to shareholders. However, if the management may believe that they are in the midst of a macroeconomic shift, they may be incentivized to invest in additional capacity. Such an expansion may be accompanied by debt. Managements may also be incentivized to invest in growth through monetary incentives or may even do so if the competition engages in similar expansion projects.

However, as the cycle turns from peak to trough, such businesses may not earn supernormal profits and would eventually earn incremental profits lower than the cost of capital. The additional costs from the new project may further hurt such returns, leading to value destruction.

Example: Suzlon Energy

Suzlon Energy, founded by Tulsi Tanti in 1995, rapidly expanded during the mid-2000s, becoming a leading global wind turbine manufacturer. Driven by the booming global demand for renewable energy, Suzlon made several strategic acquisitions, including the German company REpower (now Senvion) in 2007, to enhance its technological capabilities and market reach. However, this aggressive expansion was heavily financed through debt, leading to a substantial debt burden. Operational challenges, such as integration issues with acquired companies and technical problems with its wind turbine blades, compounded financial strain. The global financial crisis of 2008 further impacted investment in renewable energy projects, reducing demand for Suzlon’s products. Additionally, currency fluctuations adversely affected its financial stability. By the end of 2000s, Suzlon was struggling with high debt and declining profitability, leading to multiple debt restructuring processes and asset sales, including a significant stake in Senvion. Despite efforts to turn around, Suzlon continued to face financial challenges, resulting in significant losses and a reduction in market share. The expectations of growth were unrealistic and even a normal economic environment may have created challenges in delivering returns to shareholders.

Source: Google Finance

3. Poor Execution:

Managements that have realistic return expectations may still destroy value through execution failure. An example of such failure is diversification away from core competencies. While diversification itself may not be value destructive, and may even have a positive impact, diversification away from core competencies may be accompanied by significant execution risk.

Businesses with sustainable competitive advantages are rare in a universe of businesses that earn less than or equal to the return on capital. Capitalism thrives on competition, and the most effective competitors require a detailed understanding of the market, technical knowhow along with capital to compete effectively. Managements that lack expertise in a new market may still enter due to large amounts of capital at their disposal with the expectation of hiring capable management or using the current management for new ventures. However, such managements may underestimate the risks, misunderstand the competitive dynamics or the bandwidth costs to the existing business. New ventures may face subpar execution leading to subpar returns on capital invested.

Example: Microsoft in the Smartphone Market

Microsoft's entry into the smartphone market is often cited as a prime example of poor diversification. The company attempted to break into the market by acquiring Nokia's mobile phone business in 2013 for $7.2 billion, aiming to combine Nokia's hardware expertise with its own software capabilities. However, this move came too late, as the market was already dominated by Apple (iOS) and Google (Android), which had established substantial ecosystems and loyal user bases. The Windows Phone operating system struggled to attract developers, resulting in a significant app deficit compared to its competitors, which reduced consumer appeal. Additionally, the integration of Nokia's hardware with Microsoft's software was hampered by cultural and operational differences, leading to inefficiencies and slow product development. Strategically, Microsoft’s strengths lay in software, particularly in enterprise and desktop environments, which did not align well with the consumer-driven smartphone market. This misalignment, coupled with skepticism about the viability of Windows Phone, made it difficult to gain market share. Financially, the venture was disastrous, with Microsoft eventually writing off $7.6 billion related to the acquisition and laying off thousands of employees. Overall, Microsoft's foray into smartphones highlights the risks of diversifying away from core competencies and the importance of aligning new ventures with a company's existing strengths and market realities to avoid value destruction.

Summary:

While growing a business is important for creating wealth, it must be done wisely to avoid losses. Effective management, realistic goals, and good planning are crucial. Poor acquisitions, either because they are overpriced or badly integrated, and weak board oversight can hurt shareholders. Unrealistic expectations, especially in industries that go through cycles, can lead to over-expansion and high debt, which can reduce value. Additionally, poor execution, especially when moving away from core strengths, can lead to poor returns. Therefore, growth strategies should always consider the cost of capital and focus on sustainable, well-executed plans to truly increase shareholder value. Growth is not valuable by itself.

Already have an account? Log in

Want complete access

to this story?

Register Now For Free!

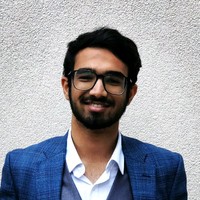

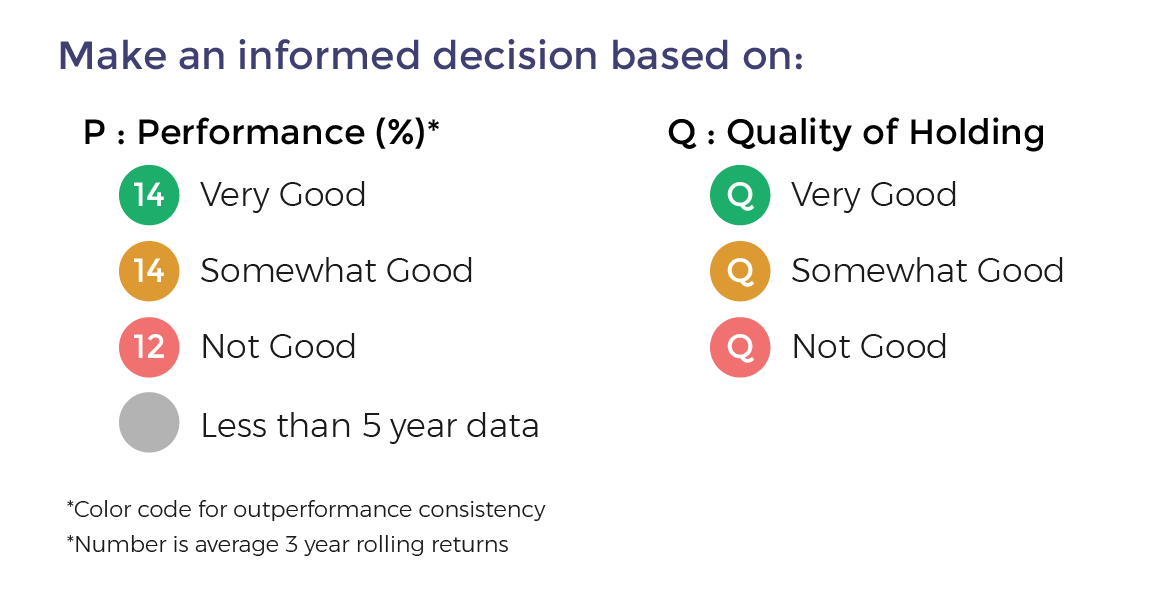

Also get more expert insights, QVPT ratings of 3500+ stocks, Stocks

Screener and much more on Registering.

Comment Your Thoughts: